The Jewish Museum in the Jewish Center Shalom Europa

The Jewish Museum in the Jewish Center Shalom Europa has a unique objective.

It focuses on the essentials of traditional Jewish life. i.e. the theological, fundamental issues as well as its implementation at home and in the synagogue.

It also portrays the allegation and confirmation in Jewish life during 900 years of Judaism in Würzburg.

The Jewish Museum invites all visitors to become acquainted with the canon of Jewish values. It encourages Jews to venture a knowledgeable orthodoxy, oriented on global Jewish life (in general), and which considers Jews to have played an important role in the cultural life of Würzburg, mainly dominated by Christianity, thus challenging the ability of the Jewish community to prosper.

The building around 1600 as shown in an engraving by Matthaeus Merian

The walls after the destruction of the building on March 16, 1945.

Wuerzburg with its Pleich quarters.

The “Landelektra” building in January 1987, shortly before demolition work started.

Reconstruction as „Landelektra“ building after 1945

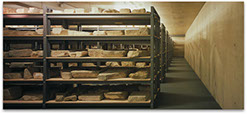

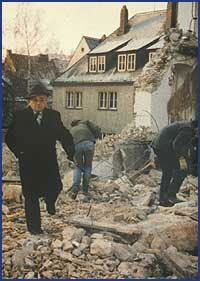

Within weeks 1505 stones and stone fragments were recovered. 70 tons in all.

Within weeks 1505 stones and stone fragments were recovered. 70 tons in all.

The late David Schuster at the construction site

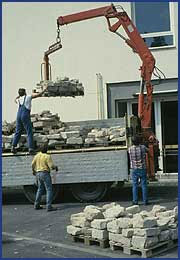

Transporting the Stones to the Rotkreuzhof

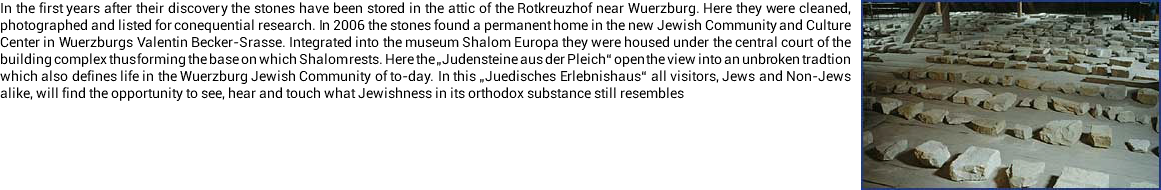

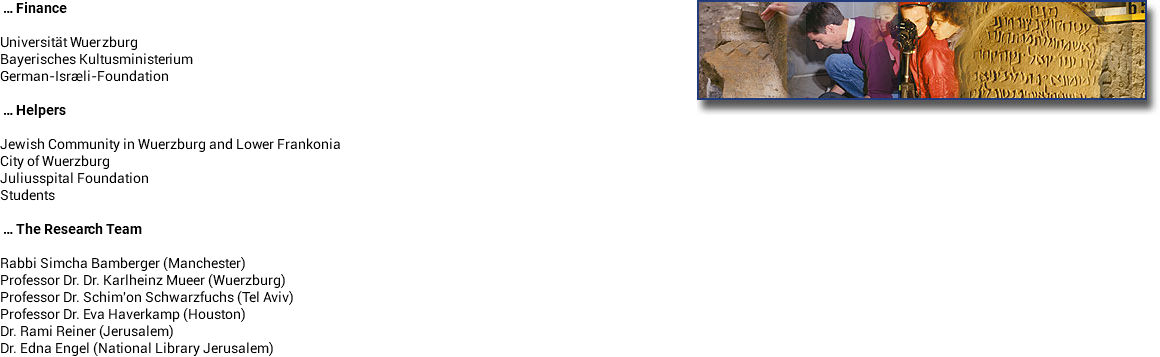

Cleaning and Photographing of the Stones

During eight semesters 175 students of the Theology Deparment at the Wuerzburg University spent 4271 manhours cleaning, registering and photographing the medieval gravestones

Two stones are changing their appearance

Two stones are changing their appearance

Gravestone for a Jew from France

„the Frenchman“ (Nr. 1288)

Marienkapelle

Gravestone for a Jew from England

(„From the Isles of the Sea“), (Nr. 999)

Gravestone for a Parnas (Nr. 815)

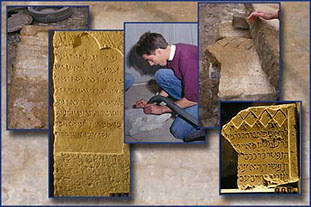

The oldest stone from between 1129 to 1138.

The latest stone, dated 1346

Site of the Cemetary (Engraving by Sebastian Muenster)

The Juliusspital as shown in its original state (emgraving by Johann Leypold, 1603)

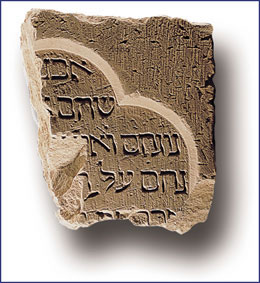

The gravestones represent an identity index of the medieval Jewish Community in Wuerzburg. They provide a cultural ranking of utmost importance. It is here where the Jewish self esteem is anchored.

The information thus gained adds up to a view of the medieval Wuerzburg as one of the great European centers of „Limmud“ and „Talmud Tora“.

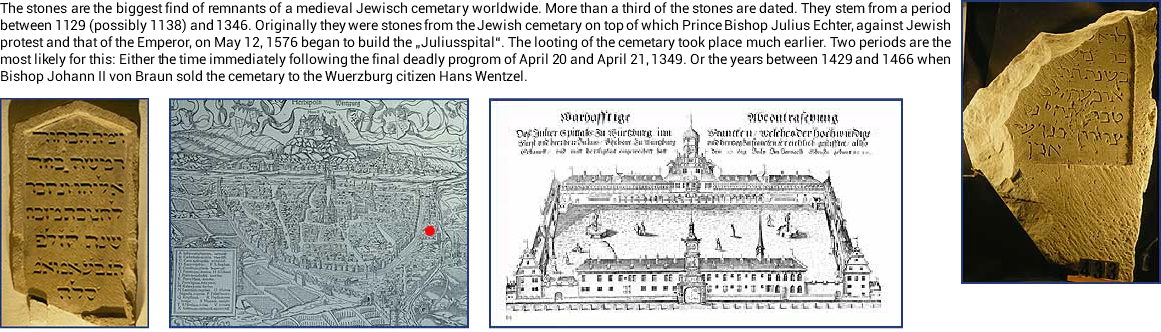

Tombstone for El’asar ben Rabbi Moscha had-darschan (who died in 1287). His father as well as he himself were widely acknowledged and respected exegetes.

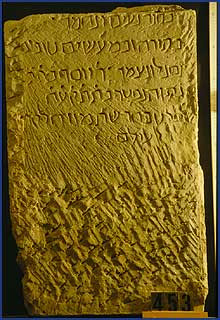

Tombstone for Schlomo ben Abraham, „Light in Exile“.This title is known to have been awarded only for one other rabbi: Gerschom of Mainz who was one of the great Halachists in the 11th century.

Tombstones for Josef ben Natan (died in 1218): famous author of synagogal prayers (Slichot and Pijutim)

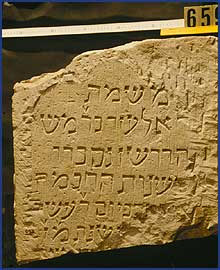

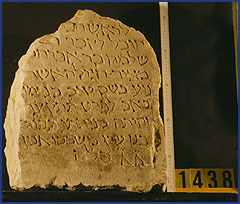

![In sorrow this stone was chiselled which was erected at the head of the honoured woman Channah, [wife of] our master, Rabbi Joël, grandson of Kehat [daughter of?] Momona, daughter of our master ben Natan. Her soul – certainly will rest well [con]tractions of birth caught her, she died in the month [...] and was no longer. Piece to her soul! She will be counted among the just women [...]](images/u92323-4.png?crc=477150174)

No viewer can escape the monumental impression of the gravestones.

No viewer can escape the monumental impression of the gravestones.The Wuerzburg artist Heide Siethoff captured this in a series of pictures which, together with a number of the stones, were first

exhibited in February/March 2000.

exhibited in February/March 2000.

– er ist traurig

und liebevoll.

Und er saeubert sie

von allem Schmutz.

Und er fotografiert sie,

eines nach dem anderen.

Und er ordnet sie an

auf dem Fußboden

in der großen Halle.

Und er ergaenzt die Grabsteine

und wendet sie einander zu,

ein Bruchstueck nahe an das andere.

Wie bei der Auferstehung der Toten,

wie ein Mosaik,

wie ein Puzzle

– ein Spiel von Kindern.

Auf meinem Tisch

liegt ein Stein,

in den man

“Amen”

ritzte

– ein Bruchstueck,

ein Überlebender

aus tausenden und abertausenden

Bruchstuecken

von zerbrochenen Grabsteinen

in juedischen Friedhoefen.

Und ich

– ich weiß,

daß alle diese Bruchstuecke

jetzt

die große

juedische

Zeitbombe

fuellen

zusammen mit

den uebrigen Bruchstuecken

und Splittern:

den Bruchstuecken von den Tafeln des Bundes

und den Bruchstuecken von Altaeren,

den Bruchstuecken von Kreuzen

und den rostigen Naegeln von einer Kreuzigung,

zusammen mit den Bruchstuecken von Haushaltsgeraeten

und Ritualgefaeßen

und mit den Bruchstuecken von Gebeinen,

und mit Schuhen

und Brillen

und Prothesen

und Gebissen

und mit den leeren Schachteln

für Ampullen mit toedlichem Gift.

All das

füllt

die juedische Zeitbombe

bis zum Ende der Tage.

Und

obwohl

ich über all das

und über das Ende der Tage

Bescheid weiß,

gibt mir

dieser Stein

auf meinem Tisch

Ruhe.

Er ist

ein Stein der Wahrheit,

der sich nicht mehr aendert.

Ein Stein der Weisheit

– weiser

als jeder Stein der Weisen.

Ein Stein

von einem zerbrochenen Grabstein

– und doch ist er vollstaendiger

als alle Art von Vollstaendigkeit.

Ein Stein, der Zeugnis ablegt

von allen Ereignissen

die seit ewigen Zeiten

geschahen

– und von allen Ereignissen,

die in Ewigkeit

noch geschehen werden.

Ein Stein des “Amen”

und der Liebe.

“Amen, Amen”

und

so geschehe sein Wille.

Uebersetzung von Karlheinz Müller